Where fashion demands the history of couturiers, menswear provokes guides. Tie rules (fold, knot), rise rules (high, pleats), shoulder rules (narrow sleeve, roman or english curve). It is between these two hegemonies that Farid Chenoune sets his 1993 Of Fashions and Men: A History of Mens Fashion.

Shorn of any edifying preface, its conceptual force is dispensed along the history it traces. It espouses tailor Chevreuil’s edict, the very same that adorns the back cover. Leiris deemed menswear a rampart: with Chenoune, ‘clothing is an idea that floats about a man’s body. ’ In 4 sections and thirty-one chapters, Chenoune draws a cosmopolitan history that has since become cliché: the modern suit emerges in England, and follows Brummel to France. Shapes grow longer at the turn of the century, and looser in its middle: tweedwoolen fabric, more or less rustic, woven with multicolored More, flannel(English flannel, from Welsh gwlanen, wool) - fabric whipped More. Volumes highlight fatigue, then leisure. Having crossed the Atlantic, menswear returns to France garbed in americanisms: teddys, suits, blazers. Chenoune shows the move from clothing to fashion: a gliding without rupture or continuity, a strange contiguity where the kernel of menswear gets lost but does not fade. It is striking to note the play of global exchange that characterises the history of menswear: the man who dresses himself, the man one dresses, is always the other man.

Chenoune found fame with a history of lingerie. The history of menswear was long a sub-history. With Of Fashions and Men, it comes to a hold, sheds its share of unsayable. The researcher elegantly closes his book by an epigraph:

“ ‘Each has his quirk, wrote Henri Calet in 1950; I have that of liking to wear clothes of varied provenance; I support a certain cosmopolitanism of dress. It discreetly reminds me of travels, adventures, far off cities or states, friends – For now, I have the italian suit, a (tattered) ‘made in USA’ shirt, moroccan socks, a swiss tie, egyptian shoes. It may be that due to this, I am exotic in demeanor.’ To one who would be tempted to pen a treatise of menswear in the spirit of this century’s end, Henri Calet’s profession of faith could be an epigraph.”

The history of menswear, by definition, only ever begins.

ANONYMOUS, the filial and heroic devotion of mademoiselle de sombreuil in september 1792. Circa. 1800.

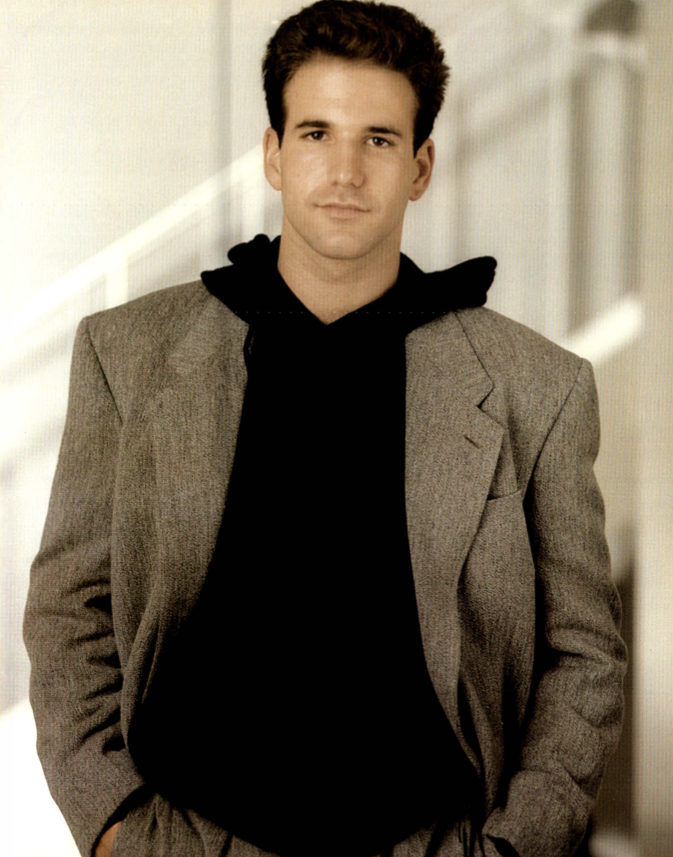

ARMANI model. 1986-1987.

CARJAT, étienne, phot. BAUDELAIRE, charles, poet. Paris. 1861.

DELAUNAY, robert, paint. portrait of tristan TZARA, writ. 1923.

‘new orleans’ evening. saint germain des prés, Paris. Circa. 1950.

HAMMERSHOI, vilhelm, paint. interior with young man reading. 1898.

Paris. Circa. 1971.

VERNET, émile, paint. self-portrait. 1835.

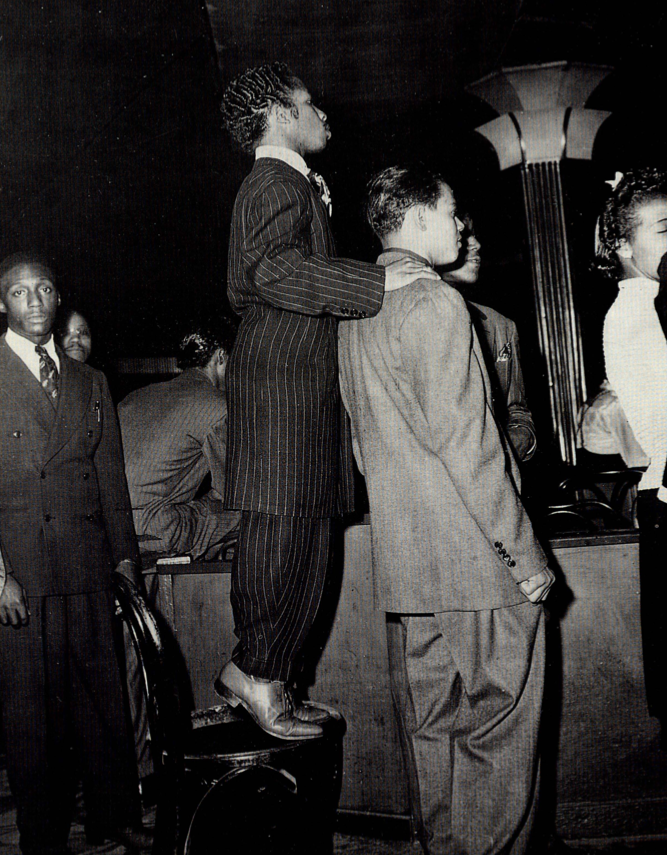

‘zoot-suits’. savoy ballroom. Circa 1938.

- The Canadian Tuxedo

- The Car Coat « Weekend style with quiet confidence—the car coat speaks without spectacle. »

- A HISTORY OF MEN’S FASHION« Chenoune shows how menswear shifts between fashion and function, individuality and universality—a history that never ends. »

- COTTON« Soft, but with weight. Relaxed, but never shapeless. It carries memory in its creases. »